Latinx LGBTQ+ spaces the government would like you to forget about

Six places that will always have Latinx LGBTQ+ heritage whether the bigots currently in charge like it or not.

You can't deport history. But the current administration is certainly trying. They deleted a whole page on Latino LGBTQ+ gathering spaces because right now there's a lot of willful fascist amnesia going around when it comes to remembering that even people who are not white and not straight have these pesky things called rights granted to them by federal law.

Unlike all the immigrants they're indiscriminately removing without due process though, we can bring this page back pretty easily. And without a court order for the executive branch to ignore!

There is one sentence from this page that we find particularly relevant to our current challenges:

"In spite of erasure and exclusion, the LGBTQ and Latino communities have preserved the symbolic and tangible remains of LGBTQ and Latino history. Even when historic places are no longer standing, art can document these stories and make the layers of history visible."

People have tried to erase these spaces before, and they did not succeed. Government control over records and websites may make them subject to bigoted whims but they will never be able to completely control human expression no matter how hard they try.

Here are are six spaces that survived, and will continue to survive as long as we have anything to say about it.

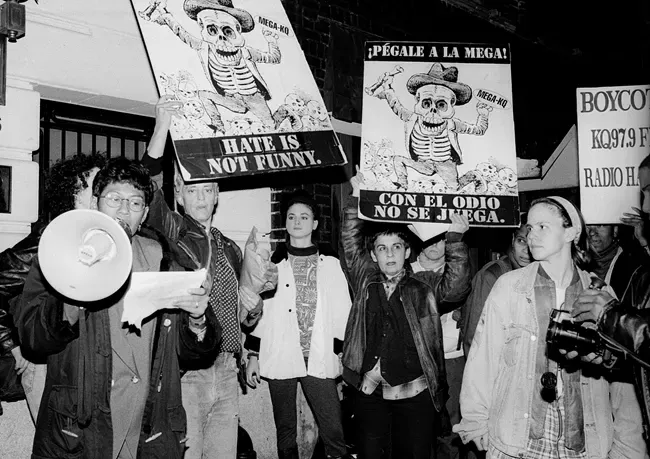

Places of Latino LGBTQ Gathering Spaces

Gathering places such as parks, people’s living rooms, and city streets are foundational to identities and communities. In these spaces, LGBTQ Latinos formed groups, found refuge, resisted oppression, and created a deeper sense of what it means to be Latino and LGBTQ.

The links on Latino and LGBTQ+ heritage have been altered on the original National Park Service website, so we're leaving the Wayback Machine links in place. The Latino article is pretty short so we'll add that one to the end of this page. We'll have to do a more thorough restoration of the LGBTQ+ heritage page though since it received that stupid "LGB" acronym treatment.

In spite of erasure and exclusion, the LGBTQ and Latino communities have preserved the symbolic and tangible remains of LGBTQ and Latino history. Even when historic places are no longer standing, art can document these stories and make the layers of history visible.

Explore the role of 6 historic places in celebrating Latino LGBTQ visibility and community in the US.

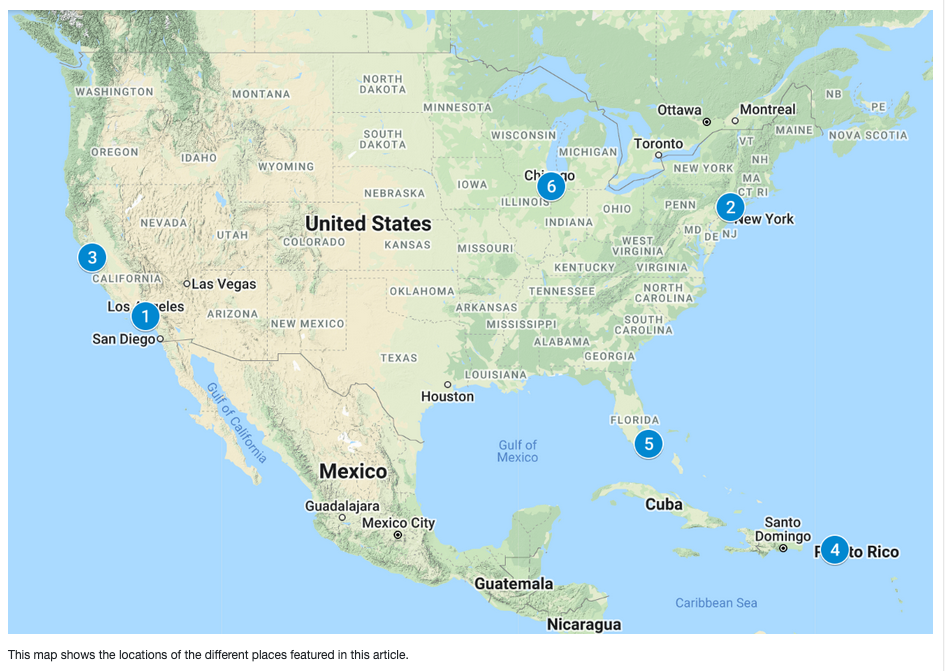

1. Great Wall of Los Angeles (Mural)

Latinos played a pivotal role in early LGBTQ activism, including two pioneering gay rights organizations.

Mattachine Society

Cuban immigrant and organizer Gonzalo “Tony” Segura, Jr. helped grow the LA-based Mattachine Society into a national organization.

Daughters of Bilitis

In 1955, Chicana activist Mary (last name unknown) cofounded the Daughters of Bilitis to create safe spaces for lesbians to socialize.

The Great Wall of Los Angeles mural depicts these events and other significant parts of LA’s history and culture. Between 1978 and 1984, Chicana muralist Judith F. Baca worked with a team of artists to create the 2,754-foot mural.

The Great Wall of Los Angeles mural was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2017.

2. The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, & Transgender Community Center

Since its founding in 1983, the LGBT Community Center in New York City has served as a gathering space for several LGBTQ groups, including the Lesbian Avengers.

Cofounded by Cuban activist and playwright Ana Maria Simo in 1992, the Lesbian Avengers used direct-action tactics (nonviolent demonstrations such as marches and kiss-ins) to increase lesbian visibility.

Simo was an experienced activist. In 1976, she and actress-director Magaly Alabau created Medusa’s Revenge. It was the first lesbian theater in New York City and the world with a permanent home, founded by and for lesbian immigrant Latinas.

The LGBT Center was designated a New York City Landmark in 2019. New York City is a Certified Local Government.

The National Park Service deleted a short essay on LGBTQ+ history in New York City in one of the hyperlinks here along with short essays about other cities as well where LGBTQ+ people thrived. We'll be restoring those essays in a separate post. The Certified Local Government page hasn't been affected. Shhhhh! No one tell DOGE!

3. The Women's Building

The San Francisco Women's Center (SFWC) emerged from radical and lesbian feminist movements in the 1970s. The SFWC purchased Mission Turn Hall in 1979 and renamed it The Women’s Building (TWB), a community landmark.

Many of the founding directors were women from various social and ethnic groups, including the late lesbian Puerto Rican activist Carmen Vazquez.

In 1994, the building’s façade transformed. A group of 7 women muralists painted the Maestrapeace Mural on the building — weaving together art, history, fiction, gender, race, class, and sexuality.

Since 1979, TWB has stood as a gathering hub for groups, such as Somos Hermanas, Ellas en Acción, and Gay Latino Alliance, who achieved and continue to achieve social and gender equality for the community.

The Women's Building was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2018.

The small essay on LGTBQ+ heritage in San Francisco they deleted in a link here will appear in a separate post. Apparently, no one told them that trying to remove the rainbow from San Francisco is like trying to swim without getting wet. Ain't gonna happen.

The Women's Building has been deleted too due to (perhaps) the triple threat of being a place that celebrated women, latinos, and sexual diversity. The listing for that place page is short, so we're going to restore it here.

Women's Building, San Francisco, CA

Quick Facts

Location: 3543 18th Street, San Francisco, CA

Significance: Social History: Women’s History and Social History: LGBTQ History, and Ethnic Heritage: Asian, Black, Hispanic, and Native American.

Designation: Listed on the National Register of Historic Places on April 30, 2018

MANAGED BY: San Francisco Women's Centers, Inc.

The Women’s Building is important in the areas of Social History: Women’s History and Social History: LGBTQ History, and Ethnic Heritage: Asian, Black, Hispanic, and Native American.

The Women’s Building (TWB) in San Francisco’s Mission District represents a powerful physical embodiment of the values and achievements of second wave feminism during the mid to late twentieth century, and the movement’s efforts to secure social justice and gender equality for women and other minorities (LGBTQ/racial/ethnic). As one of the first and longest tenured women-owned and women-operated women’s centers in the U.S., TWB represented a significant, high-profile model for the establishment and operation of similar facilities nationwide.

Women’s Centers have been identified by scholars as an extremely important property type associated with the context of 20th century women’s history and second wave feminism. In San Francisco, TWB not only served as home to the San Francisco Women’s Center’s (SFWC) diverse programs, but it also provided essential incubator space for other fledgling organizations and collaborative projects associated with women’s issues, LGBTQ concerns, and racial empowerment that bridged across multiple social themes.

Some of the organizations that operated from TWB include:

La Casa de las Madres, San Francisco's first shelter for battered women

The Women's Foundation of California

Gay Latino Alliance

The Women's Philharmonic

ACT UP/San Francisco

Bay Area Teen Voices

Lesbians Against Police Violence

Somos Hermanas

Women's Art Project

Lavender Youth Recreation & Information Center (LYRIC)

SF Women's Switchboard

Third World Women's Alliance

Lilith Theater

Women's International League for Peace and Freedom

A selection of events and artists showcased at TWB include:

Memorial for Harvey Milk

Sweet Honey in the Rock, 1979

Celebration of Black History Month, 1980

Pride Dance, 1981

Harvey Milk Birthday Celebration, 1992

Jewish Feminist Conference, 1982

Gloria Steinem, 1983

Lesbian Chorus, 1985

Alice Walker: Visions of the Spirit, 1988

Perseverance: Lesbians of Color Conference, 1988

A sufficient body of scholarship has developed to establish second wave feminism as a social movement critical to U.S. history. The Women’s Building is exceptional in this history for the scale of its ambitions, which match the large social hall it purchased in 1978 when it was founded, and for the breadth of social issues it has addressed. The period of significance for the resource is 1978 to 1994. The period of significance captures the beginnings, formation, and consolidation of TWB, culminating with the creation of the major mural project, Maestrapeace, which visually communicates the organization’s mission of supporting and celebrating women across time and around the world.

4. Edificio Comunidad de Orgullo Gay de Puerto Rico

The Edificio Comunidad de Orgullo Gay de Puerto Rico in San Juan was the home of Puerto Rico’s first gay liberation organization between 1975 and 1976. It paved the way for LGBTQ visibility on an island with deep colonial ties to machismo and anti-homosexuality.

The organization provided educational and community services and published the magazine Pa'fuera! out of Casa Orgullo’s second floor. The magazine was distributed in gay libraries like Oscar Wilde Library in Greenwich Village and Lambda Rising in Washington DC.

Casa Orgullo’s backyard extended into the city streets by hosting public events and social celebrations. These parades, pageants, and protests were key to establishing a larger community and launching the gay liberation movement in Puerto Rico.

Edificio Comunidad de Orgullo Gay de Puerto Rico was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2016.

This building wasn't deleted, but the listing was modified to erase transgender, intersex, and queer individuals. So, we're going to go ahead and give you the real, uncensored, listing right here:

Edificio Comunidad de Orgullo Gay de Puerto Rico

Quick Facts

Location: San Juan, Puerto Rico

Significance: Social History, LGBTQ

History Designation: Listed in the National Register of Historic Places - Reference Number 16000237

OPEN TO PUBLIC: No

MANAGED BY: Private

Edificio Comunidad de Orgullo Gay de Puerto Rico (Puerto Rico Community Building of Gay Pride), commonly known as Comunidad de Orgullo Gay (Gay Pride Community), is a two-story, Spanish/Mediterranean Revival apartment building in San Juan, Puerto Rico. It was founded in 1974 as the first gay/lesbian attempt to organize in order to confront the social, political and legal discrimination against the local LGBTQ community.

Inspired by the 1969 Stonewall Revolt, in New York City, and its aftermath, Comunidad de Orgullo Gay pioneered the organized resistance against the heterosexual social dominance through political action, outreach educational programs, public exposition and confrontation and social support and assistance to the local LGBTQ community. The Stonewall Revolt announced the development of a more militant and combative gay movement. Inspired by the 1960s’ civil rights struggle, the new homosexual organizations formed after Stonewall, like the Gay Liberation Front and the Gay Activist Alliance, derived their confrontational methods and political agendas. In the words of historian Martin Duberman, the events in Stonewall became “a symbol of global proportions.” In many ways, the establishment of Comunidad de Orgullo Gay de Puerto Rico reflected this national struggle.

The LGBTQ+ movement in Puerto Rico mirrors much of the struggle in other areas of the United States. Coming out of the closet in the 1960s and 1970s (or any other previous time) in Puerto Rico was not an easy task. In 1898 the United States annexed Puerto Rico. Same-sex relationships were among the first social conducts that the United States attempted to control. In 1902 the Penal Code codified same sex relationships as a crime.

During the first few decades of the twentieth century, most homosexuals in the island lived a very “heterosexual” lifestyle, keeping their sexual orientation in a very discrete, quiet, and invisible mode. It would take the economic and social conditions created by the Second World War to allow for a more visible presence of a gay community, especially within the urban context. A young labor force (male and female alike) came in contact with the new social/sexual opportunities provided by the anonymous life within the big cities.

Between the 1950s through the 1970s, these socio-economic factors prompted the formation of a gay subculture visually represented in the form of the social spaces used by the gay community: clubs, bars and public spaces used for cruising (movie theaters, hotel nightclubs, and parks, among others). With more visibility surrounding the gay subculture came opposition. In 1956, an editorial of a major newspaper warned the population about the “sexual degenerates,” “mentally sick,” “effeminate men,” which “constitute a danger to the

Young.” In 1961, Governor Luis Muñoz Marin requested a report from the Police Commissioner about the extension of the “homosexual problem” in Puerto Rico.

Even with all the conservative powers in motion against the gay population, by the late 1960s, a reformist feeling took hold among some local lawmakers that questioned the legality of the sodomy laws, indicating that they violated the rights of privacy and that the state shouldn’t have any jurisdiction in the sexual relations of consenting adults. Since 1902, Article 278 of the Penal Code penalized “acts against nature, committed with another human being or with beast,” which directly codified as a crime same sex relationship, especially among gay males. In 1974, the code was re-phrased, separating the bestiality act from the human intercourse, creating different statutes for each action. This re-rephasing was the catalyst for the creation of Comunidad de Orgullo Gay (COG) in 1974.

In order to give institutional legality to the organization, COG was properly incorporated as a non-profit organization at the Puerto Rico Department of State by Rafael Cruet, Ernie Potvin, and Paul Dirks. It became legally recorded on January 21, 1975. The Unitarian Fellowship locale became the initial meeting hall for the organization, but it didn’t last. By August 1975, COG was able to formalize the acquisition of a permanent place, renting the upper level of a 1930s commercial/residential building, in the ward of Río Piedras (San Juan). As COG’s home-base, the locale became known as Casa Orgullo.

By late 1976, after two years of a struggling but militant existence, COG disbanded. Personal and economic hardship placed an enormous pressure among the fulltime leadership and the almost fulltime volunteers that administered the various programs. Although short lived, COG was successful in many significant aspects. It created a safe haven in Casa Orgullo, where hundreds of members of the gay community were able to receive legal advice, medical assistance and moral/social support. The medical clinic at Casa Orgullo was a pioneering facility, not from the medical standpoint, but from its social approach in providing a comfortable/safe space to the gay population. Extremely significant was the organization’s efforts in creating a sense of pride, dignity and identity among the gay community through its lectures, symposiums, public appearances in radio and TV debates, and its fight against damaging public stereotypes.

While the Casa Orgullo no longer exists, its home of Casa Orgullo is privately owned. The property was the home of the organization that spearheaded, in many ways, the gay liberation movement in Puerto Rico.

5. South River Drive Historic District

The Mariel Boatlift contributed to monumental change in US immigration reform and Miami's LGBTQ history. From the early 1900s, the US denied entry to LGBTQ immigrants, but the US also opened its doors to anyone fleeing communism, including LGBTQ Marielitos who were deemed “unrevolutionary” and exiled by the Castro regime. With the Immigration Act of 1990, the US amended its immigration policy to accept LGBTQ immigrants and remove homosexuality as grounds for denying entry to the US.

Marielitos established themselves within neighborhoods like Little Havana, working in department stores and hanging out in public spaces. The visibility of the trans and gay community became more prominent as Marielitos and LGBTQ immigrants from across Latin American and the Caribbean continued to make Miami home.

South River Drive Historic District was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1987.

Looks like they're trying to delete Miami's queerness too. We'll add that essay to the separate post we're planning on cities. We suspect the current leaders of the National Park Service have never been to Miami. If they spent five minutes at the Palace, they'd know trying to eject queens and queers from that city is about as futile as playing golf in a hurricane.

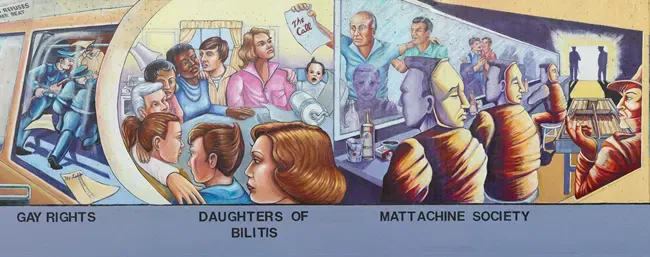

6. Chicago City Hall-Cook County Building

After being diagnosed with AIDS in 1988, Puerto Rican and Mexican political cartoonist Daniel “Danny” Sotomayor combined art with activism. He published over 200 cartoons criticizing government officials’ refusal to acknowledge AIDS and barriers to research funding, drug trials, and treatment.

Sotomayor also took to the streets as a cofounder of ACT UP Chicago. On April 24, 1990, over 5,000 demonstrators gathered to protest the American Medical Association and insurance industry’s response to AIDS. Sotomayor and other ACT UP Chicago leaders entered the Cook County Building. They hung a banner over the entrance to demand equal healthcare access for AIDS patients.

Chicago City Hall-Cook County Building was designated a Chicago Landmark in 1982. Chicago is a Certified Local Government.

The Chicago essay was deleted as well. We wish the National Park Service all the luck since Chicagoans like to be told what to do as much as they like being told that pizza doesn't have a cornbread crust. We'll add this essay to our upcoming post on cities.

The content for this article was researched and written by Melissa Hurtado, Heritage Education Fellow, and Jade Ryerson, Resource Assistant (Intern), with the Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education.

Bibliography

Baldwin, Jessica C. “The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center Designation Report.” (Designation List 513 LP-2634). NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission. Edited by Katie Lemos McHale and Margaret Herman. June 18, 2019. http://www.nyclgbtsites.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/LGBT-Community-Center.pdf.

Dowell, Chelsea. “Ana Maria Simo – Lesbian Avenger in the East Village.” Off the Grid (blog). Village Preservation. March 7, 2017. https://www.villagepreservation.org/2017/03/07/ana-maria-simo-lesbian-avenger-in-the-east-village/.

Gala, Santiago and Juan Llanes Santos. "Edificio Comunidad de Orgullo Gay de Puerto Rico." National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. Puerto Rico State Historic Preservation Office, San Juan, May 2, 2016. https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/AssetDetail?assetID=e9873242-1a04-495f-98ac-b42b47e67aab.

Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender Historical Society. "Guide to the San Francisco Women's Building/Women's Centers Records, 1966, 1972-2001." Online Archive of California. Published 2002. http://www.oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt696nb1jq/entire_text/.

Julio Capó, Jr. “Queering Mariel: Mediating Cold War Foreign Policy and U.S. Citizenship among Cuba’s Homosexual Exile Community, 1978–1994.” Journal of American Ethnic History 29, no. 4 (2010): 78-106. https://doi.org/10.5406/jamerethnhist.29.4.0078.

Keehnen, Owen. “One Person Can Change the World: Sotomayor.” In Out and Proud in Chicago: An Overview of the City’s Gay Community. Edited by Tracy Baim with contributions by John D’Emilio, Jonathan Ned Katz, and Jorjet Harper. Chicago: Surrey Books, 2008.

The Lesbian Avengers. “An Incomplete History.” About. Accessed May 24, 2022. http://www.lesbianavengers.com/about/history.html.

Library of Congress. “The Daughters of Bilitis.” LGBTQIA+ Studies: A Resource Guide. Accessed May 24, 2022. https://guides.loc.gov/lgbtq-studies/before-stonewall/daughters-of-bilitis.

Library of Congress. “The Mattachine Society.” LGBTQIA+ Studies: A Resources Guide. Accessed May 24, 2022. https://guides.loc.gov/lgbtq-studies/before-stonewall/mattachine.

Lo, Malinda. “The Women of Color Behind the Daughters of Bilitis.” Malinda Lo (blog). June 15, 2021. https://www.malindalo.com/blog/2021/6/15/daughters-of-bilitis.

Makkai, Rebecca. “They Were Warriors.” Chicago Magazine. April 7, 2020. https://www.chicagomag.com/chicago-magazine/may-2020/oral-history-act-up-chicago-aids/.

National Park Service. “Edificio Comunidad de Orgullo Gay de Puerto Rico.” Places. Last updated June 9, 2021. https://www.nps.gov/places/edificio-comunidad-de-orgullo-gay-de-puerto-rico.htm.

Springate, Megan E., ed. LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History. Washington, DC: National Park Service and National Park Foundation, 2016. https://www.nps.gov/subjects/tellingallamericansstories/lgbtqthemestudy.htm.

National Park Service. “Women's Building, San Francisco, CA”. Places. Last updated March 19, 2019. https://www.nps.gov/places/womens-building-san-francisco.htm.

NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project. “Tony Segura Residence.” Sites. Accessed May 24, 2022. https://www.nyclgbtsites.org/site/tony-segura-residence/.

Temkin, Maria, Ivan Rodriguez, and Michael Zimny. "South River Drive Historic District." National Register of Historic Inventory-Nomination Form. Bureau of Historic Preservation, Tallahassee, August 10, 1987. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/77843163.

The Social and Public Art Resource Center in LA. “The Great Wall – History and Description.” Programs. Accessed May 24, 2022. https://sparcinla.org/the-great-wall-part-2/.

Latina/o Gender and Sexuality

By Deena J. González and Ellie D. Hernández

Introduction

Gender and sexuality among US Latina/o populations encompass a continuum of experiences, historical, cultural, religious, and lived. Gender and sexuality varied by culture or ethnicity and by era across the many different Latino populations descended from Latin Americans. Latino national histories, born inside the thirty-three different Latin American countries in existence today, are united in one irrefutable link to the conquest, by Spain. The Spanish and Portuguese warred against many indigenous empires, towns, and communities encountered in 1519, and the wars continued subsequently into the 1800s, during the colonization of the Americas by other countries, including the United States.

When in 1519 the Spaniards landed on the Veracruz shore and made their way into what was the most populated city in the Americas, Tenochtitlan, and in the two years it took for them to lay claim to what would become México City and its environs, gender and sexuality played a key role among people who survived the conquest and those who as conquerors remained in México as well as in Central and South America to create nations across three centuries of time (from 1521 to 1898). A primary example is Malintzin Tenepal (Malinche or Doña Marina as the Spanish called her), the mistress and lover of the conqueror, Hernán Cortés, who had two children with him. From the outset this racial and ethnic mixing of people known as mestizaje shaped gender and sexuality, because it imbued the outcomes of these unions, many of them violent, with legal, economic, and sexual consequences. Gender and sexuality were foundational in the story of Malinche and Cortés because the woman was memorialized as the mother of the first mestizo children of the Americas, which was not the case, but also as the supreme betrayer of the Mexicans. Read more » [PDF 3.0 MB]

The views and conclusions contained in the essays are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Wayback Machine link

As usual, please have a look at the Wayback Machine link for yourself if you'd like to see the original, uncensored source material for this article.

Places of Latino LGBTQ Gathering Spaces: https://web.archive.org/web/20240927202942/https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/places-of-latino-lgbtq-gathering-spaces.htm